In 2019, about two years ago, I discovered the Game B movement. As I learned more about it, from time to time I encountered reference to the Dunbar Number. Below is a quote from the Game B Wiki.

In 2019, about two years ago, I discovered the Game B movement. As I learned more about it, from time to time I encountered reference to the Dunbar Number. Below is a quote from the Game B Wiki.

Humans Found Coherence Under the Dunbar Number

With this new collective intelligence toolkit, groups of humans gathered at the band level numbering between 5 to 150. These groups were meta-stable due to the high level of coherence and ability to police defection. Robin Dunbar found a correlation between primate brain size and average social group size and proposed that for humans, 150 appears to be the limit of our neurological capacities to model every other member and all of the complexities of relationships. At 150, Dunbar speculated that 42% of the group’s time would need to be devoted to social grooming.

As Jim Rutt hypothesizes, a band that could have coherence at 150 had a very substantial advantage over a band that could only have coherence at 80, so there was a group selection advantage. There was a ratchet for more neocortex until the limit of the pelvic girdle in the human female was reached and that was how he converged to the Dunbar number of 150.

As examples, Dunbar found 150 as the estimated size of a Neolithic farming village; 150 as the splitting point of Hutterite settlements; 200 as the upper bound on the number of academics in a discipline's sub-specialisation. As bands approach 150, they tended to fractionate into two units.

With high degrees of coherence under 150, humans very quickly became asymmetric with the rest of nature. This allowed humans to spread, survive, and thrive in most environments. We quickly became the peak predator. Ever since this Cognitive Revolution, humans have been able to change our behaviour quickly, transmitting new behaviours to future generations without any need for genetic or environmental changes. So, the speed of evolution became dominated by cultural evolution rather than biological evolution

A few months ago, Robin Dunbar was a guest at The Stoa. I watched the YouTube video, Dunbar's Number w/ Robin Dunbar May 27, 2021 and I thought that he was thoughtful, reasonable and pleasant. He made a good impression on me.

Consequently, when I became aware of his book, Friends: Understanding the Power of our Most Important Relationships, I decided to read it. Recently I had experienced some challenges with interactions with a good friend and the topic of friendship was on my mind. I hoped to gain some deep insights from Robin Dunbar.

The early chapters of Friends were disappointing. I kept reading but it did not get better. In this book report I will try to capture some of my reactions and criticisms.

Of course, I do agree with Dunbar on the importance of friends.

...having no friends or not being involved in community activities will dramatically affect how long you live.

Being part of a group makes us feel properly human. We feel more relaxed when we know we belong. We feel more satisfied with life when we know we are wanted.

My reactions to Dunbar may be unjustified. I hold the following opinions lightly, mostly wanting more information. But I am not motivated to do more research at this time.

Stated bluntly, Dunbar’s Number does not seem to me to be a profound insight. “...humans can comfortably maintain 150 stable relationships.” Really? A big deal?

That there might be an evolutionary dimension to this is suggested by the fact the loneliness has been linked to both the oxytocin receptor genes (at least in adolescent girls) and the serotonin transporter gene – two neurochemicals in the brain that play an important role in regulating social behaviour. People who carry one particular variant of these genes are more likely to experience loneliness even in the middle of a crowd.

It seems to me that Dunbar has a simplistic view of the role of neurochemicals in the brain. Likewise, I am skeptical of the linkage between particular genes and the experience of loneliness. I would be interested in what experts in these areas have to say.

Nonetheless, after many hours of hard work, we had a set of brain scans and matching network questionnaires. It was just a matter of seeing which bits of the brain increased in size most with the number of friends…. The fact that the amygdala has been flagged up in several of the studies is interesting.... She looked at the brain’s white matter and showed that its volume was also correlated with the size of the friendship circle.

Dunbar has lots to say about brain scans and correlations. I have considerable skepticism about the useful information generated by such information and would like to hear from experts. Again, “just a matter of seeing which bits of the brain increased in size” seems overly simplistic to me.

Throughout the book, the way Dunbar discussed men and women irritated me.

One of the things we had noticed in our various studies of social networks was that women always had slightly more friends than men.

A woman’s best friend is an intimate, someone to confide in and seek advice from; a man’s best friend is just someone to spend an evening in the pub with.

He had only two discrete groups, men and women. He seemed to give only token acknowledgement of the differences within these groups, which I believe to be very significant. Moreover, personally I do not fit his profile of the typical man nor does my wife fit the profile of a typical woman. All of my life experience rebelled against his characterizations.

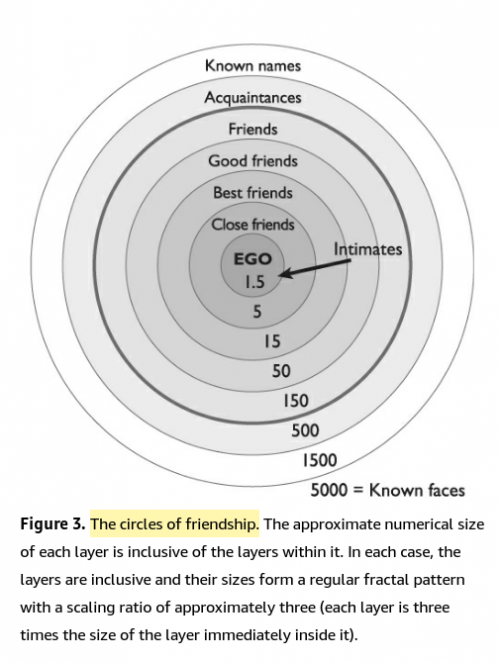

As I consider the regular fractal pattern, I can’t help but think: If you look for a pattern, you will probably find one. I am not saying that Figure 3 has no value. But I think Dunbar makes more of the numbers than is warranted.

As I consider the regular fractal pattern, I can’t help but think: If you look for a pattern, you will probably find one. I am not saying that Figure 3 has no value. But I think Dunbar makes more of the numbers than is warranted.

The next four chapters examine the mechanisms involved and explain just why we cannot have social circles of limitless size.

I do not need four chapters to understand why I cannot have a social circle of limitless size. We are finite beings with many limitations. I now found myself wishing Dunbar to be more concise.

To be fair, although I find Dunbar’s book simplistic, he does hint at complexity from time to time.

The human social world is possibly the most complex phenomenon in the observed universe – far more complex than the mysterious processes that create stars and engineer the orbits of the planets.

But, as I read the following sentence, I cannot shed my skepticism. Perhaps this reflects more on me than Dunbar. But of what value is knowing this? Does anyone know anything about their own genes? It seems to me that the nature-nurture debate remains important but inconclusive.

The results were very clear. By far the best predictor of the quality of people’s romantic relationships (and, in particular, their degree of promiscuity) was their oxytocin-receptor genes.

This brings us to the last piece of our jigsaw puzzle, the Seven Pillars of Friendship. This is the subject of the next chapter.

• having the same language (or dialect)

• growing up in the same location

• having had the same educational and career experiences (notoriously, medical people gravitate together, and lawyers do the same

• having the same hobbies and interests

• having the same world view (an amalgam of moral views, religious views, and political views)

• having the same sense of humour

• having the same musical tastes

Well, this is interesting but, intuitively, this does not seem to capture the essence of friendship, at least not for me.

So let us see what romance can tell us about friendships.

Evolutionary psychologists have conventionally held to the view that, on average, women tend to be more monogamous and men more predisposed to be promiscuous, and broadly speaking there is a lot of evidence to support this split.

I am content to not be the average man.

As in our study, he found that males preferred to engage in physical activities rather than conversation.

And again, if I took him seriously, Dunbar would irritate me. I, a male, have always preferred conversation to physical activity. And I have had, and continue to have, a significant number of friendships with other males that have centered on our conversations.

At the same time, we should not overgeneralise. The fact that there are deep-rooted sex differences in social style does not mean that there are differences in all traits.

Yet, overgeneralise is what Robin Dunbar seems to do.

In our relationship breakdown survey, we offered respondents eleven reasons why a relationship might fail. Ranked in order of most to least frequent in their responses, they were: lack of caring, poor communication, drifted apart, jealousy, problems with alcohol or drugs, anxiety about the relationship, competition from rivals, ‘stirring’ by other people, tiredness, misunderstandings and cultural differences between the couple.

Some of these factors are evident in my friendships. But the single biggest factor affecting my friendships was moving from Calgary, Alberta, Canada to Ajijic, Jalisco, Mexico in 2012. And now my relationships, particularly with family, are being impacted by deep differences of opinion on issues related to the coronavirus pandemic.

So, in the final chapter of this story of friendship, let’s turn to see what opportunities the digital world and social media have to offer, both for the current older generation and for the future prospects of the younger generations that have grown up with the internet.

The negative observation has been just how poorly applications like Zoom and Skype actually work for large social groups… it’s not obvious that it really functions well as a conversational medium for more than three or four people.

Based on my personal experience since the start of the pandemic, I strongly disagree. Better than thinking about either large or small groups is thinking about both large and small groups. I have been to events via Zoom that included both a single large group and breakouts into small groups. The results were excellent. And I am currently building new friendships via Zoom that are already as good as some of my long-term relationships.

A few years ago I may have been more impressed by Friends: Understanding the Power of our Most Important Relationships by Robin Dunbar. But in 2019 I discovered the Game B movement which has an abundance of very intelligent and very deep and broad thinkers. They understand complexity, emergence and much more. And they seem quite humble, very aware of what they do not know. In contrast, Robin Dunbar seems to be merely a respectable and successful Game A player somewhat overly impressed with his own contribution to the body of knowledge available to us.