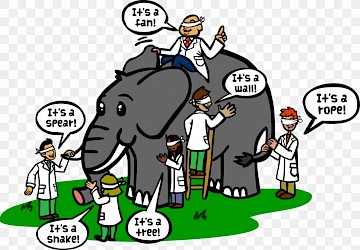

Imagine six blind men each feeling one, and only one, part of an elephant. One man examines its trunk, another the tusk, another an ear, another its side, another its leg and lastly, another its tail. Each man believes he accurately describes the elephant and that the other men are somehow mistaken. Discussion accomplished nothing. In the parable the men each believed the others were lying and they came to blows over their sense of reality.

Imagine six blind men each feeling one, and only one, part of an elephant. One man examines its trunk, another the tusk, another an ear, another its side, another its leg and lastly, another its tail. Each man believes he accurately describes the elephant and that the other men are somehow mistaken. Discussion accomplished nothing. In the parable the men each believed the others were lying and they came to blows over their sense of reality.

The moral of the story is obvious and yet such dysfunctional behavior is on display daily.

The parable of the Blind Men and an Elephant originated in ancient India over 2500 years ago. Although the story has survived for centuries, its wisdom seems lost in the world today. And, like many narratives, it no longer seems adequate and perhaps it needs an update.

Buckminster Fuller introduced the idea of a knowledge explosion, something we all have experienced in our lifetime. He noted that by 1900 it took about 100 years for knowledge to double. Fifty years later knowledge was doubling four times faster. Today knowledge may be doubling every year. This creates an exponential curve, a term we have become familiar with as we learned about coronaviruses.

In theory six blind men could easily describe an elephant. If each understood the reality of their own perspective, and that of all the others, working together instead of arguing and fighting, a reasonably accurate description would soon emerge. However, if we think of the elephant as symbolic of the knowledge which explains our world today, six people with their eyes wide open and a willingness to work cooperatively would still face an almost impossible task. Every human being has easy access to vast quantities of information and the knowledge we each have is unique to us. And every human being has a different experience of life through which they filter information. It has never been more difficult to come to a common understanding. And it has never been more important that we do so.

Marcelo Gleiser in his book The Island of Knowledge: The Limits of Science and the Search for Meaning asserts that the best we can do is create a convincing illusion that we understand the world we live in. We each live on our own little island of knowledge surrounded by an ocean representing what we do not know. With each passing year that ocean becomes bigger and we become more isolated.

Two events in 2016 taught me that there was much about the world I lived in that I did not understand. I did not anticipate the outcome of the Brexit referendum in June nor the election of Donald Trump in November. For the next two or three years I worked hard at better understanding these major disruptions. Today I have much more knowledge about these events and the conditions that lead to them. But, most importantly, I have gained a deeper understanding about how little I know.

Now in 2020 the whole world is trying to better understand an even bigger disruption. In December 2019 I knew very little about viruses and nothing about coronaviruses. That soon changed and I began documenting my experience in 2020 March. I read and read and read but I could not keep up with a flood of information. Nevertheless, I was able to create a new, convincing illusion of knowing that is sufficient for my sense of being competent to live in this new world.

All we need to do today to gain a little knowledge is go to Wikipedia. We can learn much there, and we can be quickly overwhelmed. Let’s stick our toe in the water.

...millions of different types, although only about 5,000 viruses have been described in detail.

And look at all the links to more information!

And I am overwhelmed with information about misinformation!

Misinformation related to the COVID-19 pandemic

The pandemic of the coronavirus disease 2019 has caused a large number of conspiracy theories and misinformation about where the pandemic started, how serious it is and the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment.

But viruses are only a small part of a bigger picture.

The best path forward is not based on gaining more knowledge. But maybe there is a way. What if we all admit to how little we know, or can know. What if we all admit that the best we can do is to create our own convincing illusion. What if we give up on seeking certainty and fully embrace uncertainty instead. What if we let go of our need for a common understanding and learn to live well with others who have different illusions. What if we reduce our emphasis on objective knowledge and increase our emphasis on sharing our subjective lived experience.

And wouldn’t it be great if some creative writer wrote a modern parable to replace the the Blind Men and an Elephant.