I knew a little bit, only a little bit, about infectious diseases before the coronavirus crisis.

I knew that five hundred years ago the indigenous population of North and South America had been devastated because of a lack of immunity to the diseases brought by the Europeans. I knew that far more people died from infectious disease than as a result of the wars of conquest. The estimates vary widely but the numbers are staggering, millions, many millions. Some historians suggest that up to 95% of the native population succumbed to diseases with the high end of ranges reaching one hundred million people. One of those diseases was smallpox.

I learned a lot about smallpox from reading Searching for Sitala Mata: Eradicating Smallpox in India by Connie Davis, a member of the book club I launched in 2016. The eradication of smallpox with vaccines is one of the great success stories of the second half of the twentieth century. Today, almost no one worries about smallpox, only a few who worry about its possible recreation for use in biological warfare.

I remember being vaccinated on several occasions at school as a boy growing up in Nova Scotia in the 1950s and 1960s. I do not know for what I was vaccinated, probably smallpox and polio and other infectious diseases. I remember something other than a needle in the arm, a different device, used for one of those threats. I do not remember being aware of any resistance or controversy at that time. I am unaware of anyone today asserting that those vaccination campaigns were anything but a great success with benefits far exceeding any harm.

Currently I am reading a nonfiction book set in the 1800s. Medical practice at that time was still very primitive. Children and adults often died from infectious diseases. I am very grateful that I was born in 1951 and that I benefited from the incredible advances made in the fifty years before I was born, including the development of vaccines. Everyone should at least skim Diseases and epidemics of the 19th century in wikipedia and be informed.

All current issues should be understood in a historical context. The mainstream media does a very poor job of providing that. But we are free to educate ourselves.

Early in the pandemic, as I tried to understand the magnitude of the change I was living through, I became very annoyed with CNN. I was soon tired of hearing about the importance of following the science over and over and over again. The admonition was not wrong, but it was unbalanced and incomplete. From the beginning of the pandemic, it seemed to me that the economy was also very important. But since its launch in 1980, CNN had drifted far from its roots as a credible, 24/7 cable news network. It has become a player in the cultural wars.

In 2019 I gained an insight that significantly changed my worldview. I began to understand civilization as a tangle of deeply intertwined complex systems that were in aggregate very fragile. I discovered some thinkers who applied this framework to the problem of global warming. The inhabitants of the earth had an unsolvable problem. Save the planet and kill the economy. Save the economy and kill the planet. Either way civilization fails, unless we find another way.

At one time some thinkers thought that the global warming crisis would be a unifying issue for all the inhabitants of the earth. Clearly, they said, we are all in this together. But year after year the problem grew.

Early in the latest crisis a few thought leaders saw the threat of the novel coronavirus as an opportunity to accomplish what climate change did not. Again, obviously, we were all in this together, all facing the same common problem of this new infectious disease. It made sense to think and act globally as viruses have no respect for borders between countries. Novel coronavirus would be the great unifier! That thinking did not last long.

Instead, how to respond to a new threat quickly became one more issue to use as ammunition in the culture wars. From the start, positions were taken based on the political interests of deeply divided parties. Once again, polarization got worse. And the mainstream media took sides, CNN and others on one side and FOX and others on the other side. Social media amplified the noise and good signals from reliable sources became almost impossible to notice.

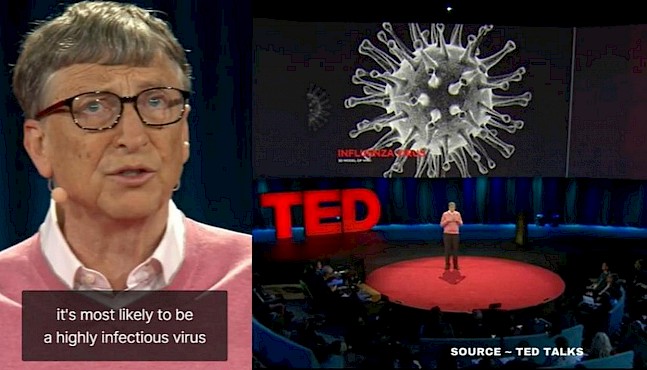

Near the end of March, 2020 I listened to the now famous Bill Gates TED talk given in 2015, The next outbreak? We're not ready, which now has over 40 million views. We were warned, but we did not listen. Why not? The answer is complex and I will only make a couple of simple points. Generally, people were either unaware of the video (I was not) or did not trust Gates (I would not). I think Bill Gates is very intelligent, very well educated and motivated by good intentions. Because of his work through the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation I think he can rightly claim to be an infectious disease expert. I saw some of his contributions on CNN in 2020 and I thought he added a lot of value. But, intuitively, I do not think Bill Gates is a wise man. Intuitively, I think he and I would have significant differences in our worldviews. I think Bill Gates sees the world through the very narrow lens of a billionaire, committed to the system that made him rich.

Near the end of March, 2020 I listened to the now famous Bill Gates TED talk given in 2015, The next outbreak? We're not ready, which now has over 40 million views. We were warned, but we did not listen. Why not? The answer is complex and I will only make a couple of simple points. Generally, people were either unaware of the video (I was not) or did not trust Gates (I would not). I think Bill Gates is very intelligent, very well educated and motivated by good intentions. Because of his work through the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation I think he can rightly claim to be an infectious disease expert. I saw some of his contributions on CNN in 2020 and I thought he added a lot of value. But, intuitively, I do not think Bill Gates is a wise man. Intuitively, I think he and I would have significant differences in our worldviews. I think Bill Gates sees the world through the very narrow lens of a billionaire, committed to the system that made him rich.

But Bill Gates does not deserve his fate in fighting infectious diseases. He has become the subject of conspiracy theories and a pawn in the culture wars. He has become click bait and is used to invoke outrage. Being for or against Bill Gates has become a signal of our tribal loyalties. The good things he says, the good signal, has been lost in the noise.

Likewise, 80 year old Tony Fauci, probably the top infectious disease expert in the USA, has been made into a highly divisive caricature of himself.

Early in the pandemic, news reports indicated that the US intelligence services had warned the government and the citizens of the threat posed by infectious diseases. I decided to look at the report itself, as I sometimes do, rather than trust media reporting. The report, Worldwide Threat Assessment of the US Intelligence Community, was dated February 19, 2016.

Infectious diseases and vulnerabilities in the global supply chain for medical countermeasures will continue to pose a danger to US national security in 2016. Land-use changes will increase animal-to-human interactions and globalization will raise the potential for rapid cross-regional spread of disease, while the international community remains ill prepared to collectively coordinate and respond to disease threats. Influenza viruses, coronaviruses such as the one causing Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), and hemorrhagic fever viruses such as Ebola are examples of infectious disease agents that are passed from animals to humans and can quickly pose regional or global threats. Zika virus, an emerging infectious disease threat first detected in the Western Hemisphere in 2014, is projected to cause up to 4 million cases in 2016; it will probably spread to virtually every country in the hemisphere. Although the virus is predominantly a mild illness, and no vaccine or treatment is available, the Zika virus might be linked to devastating birth defects in children whose mothers were infected during pregnancy. Many developed and developing nations remain unable to implement coordinated plans of action to prevent infectious disease outbreaks, strengthen global disease surveillance and response, rapidly share information, develop diagnostic tools and countermeasures, or maintain the safe transit of personnel and materials.

Infectious diseases get one paragraph in a 33 page report. The report is a comprehensive summary of all threats facing the USA. The report makes no attempt to elevate the threat of infectious disease as a clear and imminent danger. Of course, that could only be done with hindsight. The mainstream media did not provide any context for this report, and other such reports, beyond the coronavirus crisis. In my opinion, it is the allocation of resources for threat mitigation that is also important. But the threats quickly overwhelm available resources. In my opinion, understanding risks and accepting uncertainty is necessary for societal and individual wellbeing.

I have come to believe that as a society, as a civilization, one of our greatest challenges is finding common ground, somehow transcending our current alternative views of reality. The problem is far deeper than finding common cause against a virus. Mask or no mask, open or close businesses, travel or not merely are choices that reflect very different views of the world we live in. And most people seem oblivious to these dynamics, as was I for most of my life.

Like many others, I see all of this reflected in my family and friends. Most of them, like most people, are just trying to do the best they can under the circumstances. But one of my relatives is clearly completely in the grip of conspiracy theories. In these uncertain times, more people are finding the illusion of certainty in the wrong places.

Personally, I did not hesitate to be vaccinated for protection against COVID-19, and with the sinovac vaccine at that. I am not certain that I am doing the right thing, but it is not certainty that I need. My decision is highly intuitive, doing the best I can with what I know. All things considered, weighing the potential risks of being vaccinated or not, I am at peace with my decision.

I am even strangely at peace with observing the growing menace of polarization. I try not to be triggered by players on both sides of any issue. I am trying to be the change I want to see in the world.